Overview

The trolley problem has long served as a cornerstone of ethical thought experiments, challenging individuals to grapple with morally complex decisions. With the rise of digital platforms, this once-academic dilemma has found new life in viral videos and online discourse. In this post, we explore a series of modern trolley problem variants, analyzing the ethical frameworks behind each response and examining the deeper philosophical implications that go beyond numbers and lifelines.

The Classic Dilemma: Numbers vs. Action

The classic trolley problem asks: would you pull a lever to divert a runaway trolley from killing five people, knowing it will kill one person on another track? The majority viewpoint leans toward actionpulling the lever to sacrifice one and save five. This response aligns with utilitarian ethics, which focus on minimizing total harm. However, even this seemingly simple dilemma sparks debates about agency, responsibility, and whether actively choosing to kill one is morally superior to passively allowing five to die.

When Incentive Enters: Adding Money to the Equation

Now imagine the person on the track offers $500,000 to be saved by diverting the trolley onto another person. The majority reject this offer, demonstrating a clear discomfort with commodifying life. The ethical concern shifts from numbers to motivationsthe idea that accepting money in exchange for someone else’s life is inherently corrupting. It transforms a principled decision into a transaction, drawing a stark line between moral reason and moral corruption.

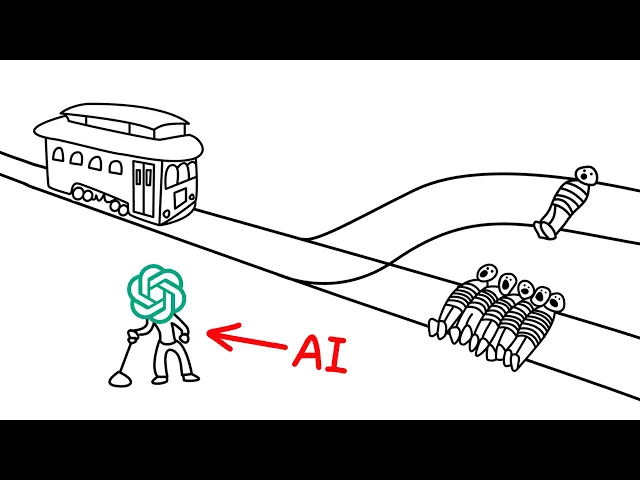

Non-Human Lives: Animals and Artificial Intelligence

Other variations ask us to weigh lives across species. Would you save five lobsters by sacrificing a cat? Would you save five sentient robots by sacrificing a human? These hypotheticals introduce questions about the value of consciousness, speciesism, and the ethics of artificial life. Many lean toward saving greater numbers, but others advocate for the uniqueness of human life or the complexity of individual consciousness, drawing moral boundaries around different forms of sentient life.

Intention, Consent, and Accidents

In scenarios where five people intentionally tie themselves to tracks, the equation becomes more nuanced. Are their lives worth saving more than an unsuspecting individual who tripped into harm’s way? Responses varied. Some believe that informed consent changes the moral responsibility, defending the innocent. Others stick with a utilitarian perspectivesaving five still outweighs one, regardless of intention. Here, moral priority shifts from outcomes to originshow people arrived in their predicaments matters deeply to some.

Unknowns and Uncertainty: Decisions Without Clarity

What if you can’t see clearly due to missing glasses, or the effects of an action are probabilistic (e.g., the trolley might kill people 100 years from now)? Here, responses reveal a recurring theme: uncertainty often discourages action. Many hesitate to act without clear data, fearing causing harm based on incorrect assumptions. Others argue that probable reduction of harm still justifies a calculated risk. This emphasis on certainty highlights how much people prioritize confidence in their moral calculus.

In a unique twist, the trolley can reduce five people’s life spans by 10 years each or one person’s by 50 years. Almost universally, responders opt for minimizing individual impact, even if total life years lost are equal. This introduces distributive ethics: sharing the burden is often seen as more humane than delivering a concentrated blow to a single life, emphasizing fairness and compassion over sheer arithmetic.

The Value of Life: Age, Virtue, and Identity

Age and morality also factor in heavily. Would you sacrifice a baby to save five elderly people? Or save a good citizen over a litterer? Several respondents mention the symbolic and societal contributions of individuals. Despite discomfort, many lean toward valuing societal impact and innocence, though not without ethical unease. Moral worth varies in human eyes, even if philosophically it’s supposed to be equal. These scenarios expose the often unspoken hierarchies in how people value different human lives.

Existential Endgames: Eternity, Reincarnation, and Determinism

Some trolley problems are deeply abstract: the trolley is caught in a time loop or you’re everyone due to reincarnation. These thought experiments elevate the discussion from interpersonal ethics to metaphysical contemplation. Would you end suffering by triggering an explosion, or preserve hope through eternal looping? Is choice even real if the universe is deterministic? Answers vary, but even those who believe in fate still find meaning in the moment of decision. This reflects a human desire to preserve agency, even when philosophically uncertain.

Conclusion

The trolley problem, in all its forms, serves as a mirror to our collective moral compass. Whether it’s the classic five-versus-one dilemma or newer twists involving babies, robots, or long-term consequences, these scenarios challenge us to balance empathy, logic, and philosophical principle. We see recurring themes: utilitarianism, deontology, value of life, consent, uncertainty, and fairness. There’s rarely a consensus, but the importance lies in the thinking each variation provokes. The trolley problem remains relevant not as a question with one answer, but as a gateway into the ethics of being human.

Note: This blog is written and based on a YouTube video. Orignal creator video below: